Amba Sayal-Bennett | Anatomy of parts

15 March - 19 April 2025

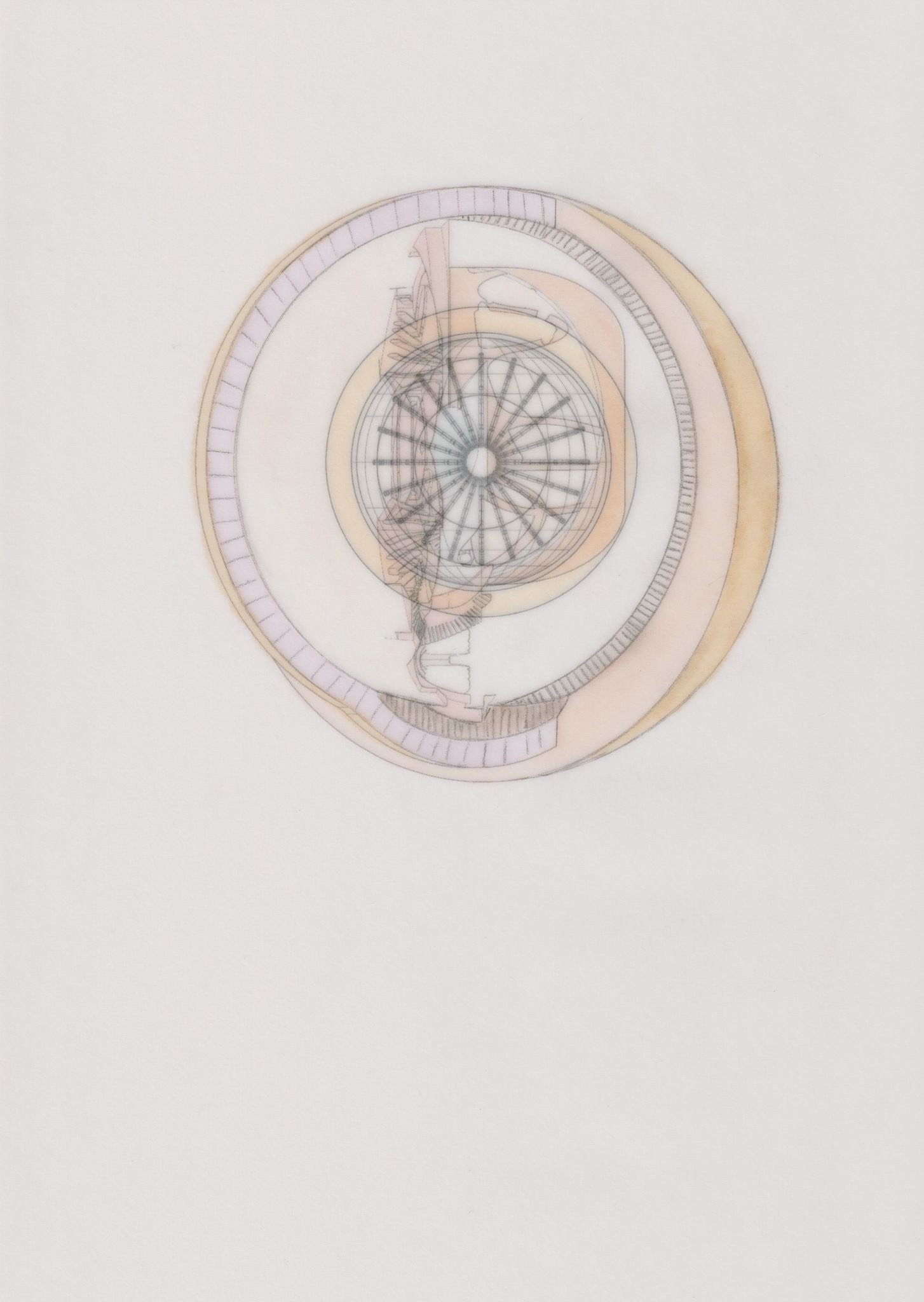

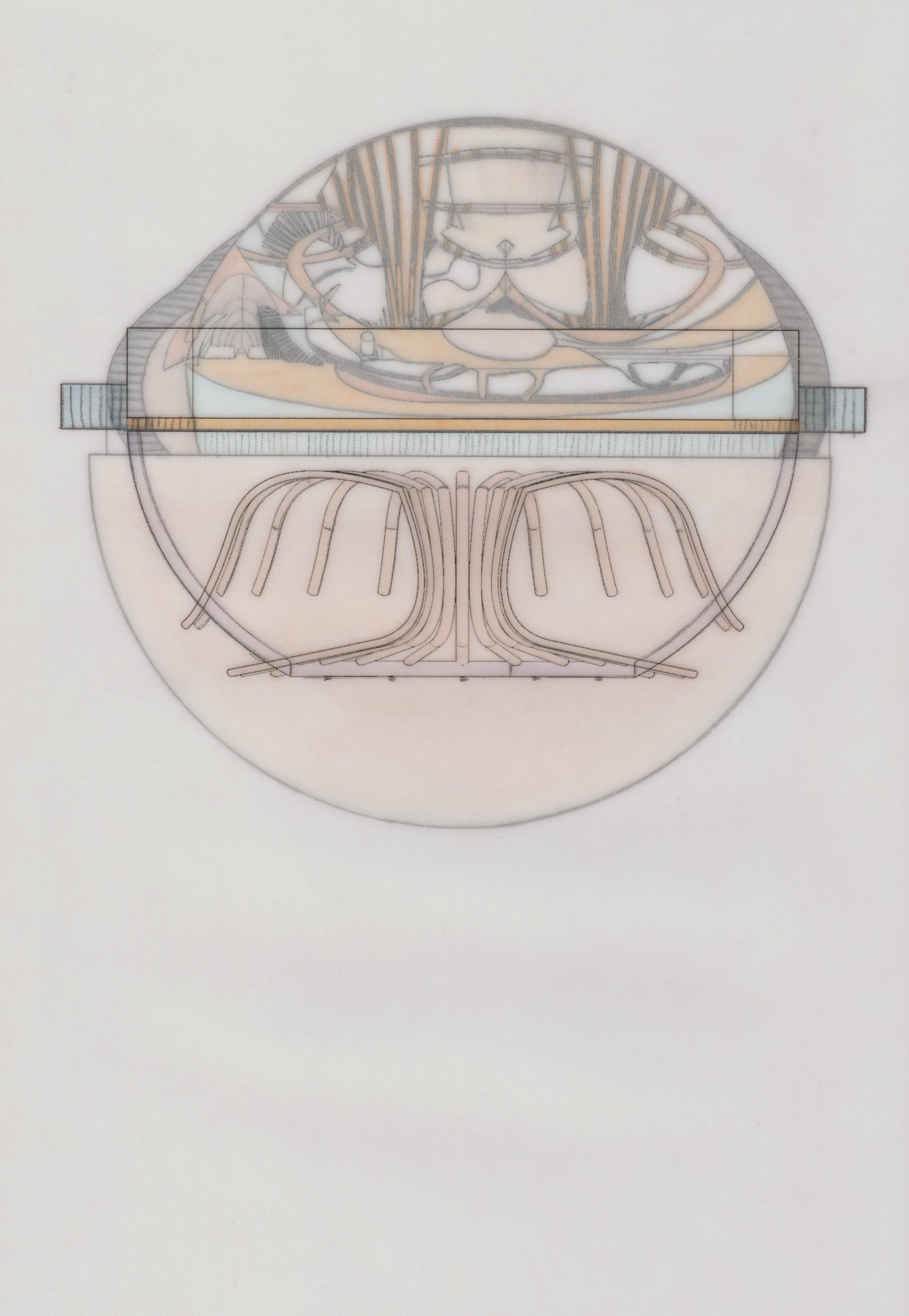

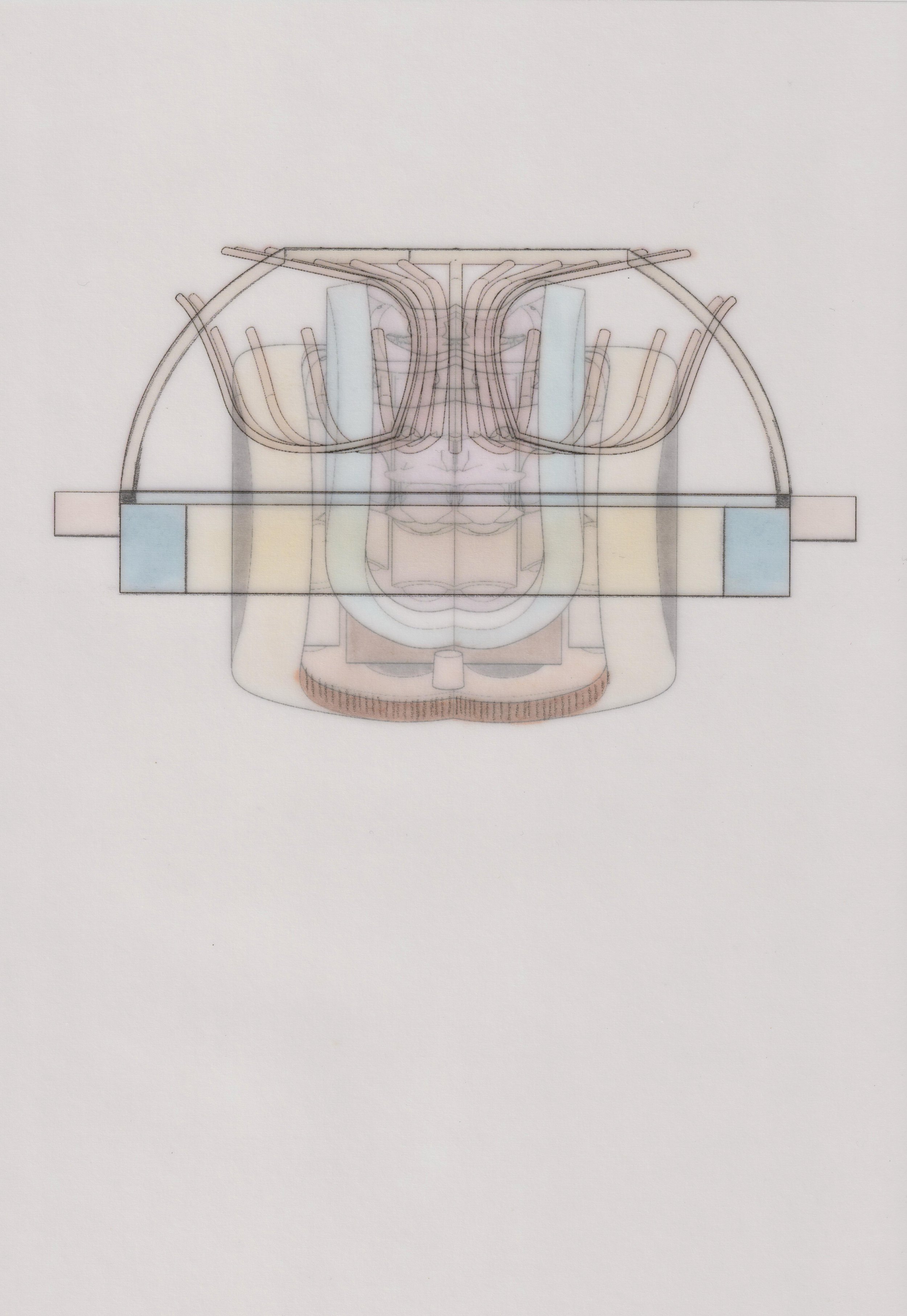

The placement of a cut determines the divide. For artist Amba Sayal-Bennett, this deceptively simple statement yields a host of inter-laced problems. Early in her arts education, Sayal-Bennett found herself presented with a parcelled cadaver; an enthused professor teaching anatomy drawing would have it that her class created studies directly from the dissections of medical students. This encounter – rather, a paroxysm confounding the abstract and the literal – the artist doubles back to for its undeniable uncanniness: 1. the brutality of cutting that exposes and lays bare; 2. the power of looking to de-subjectivize the human body, render it object. It transpires that cutting is not only for and of the body; objects reveal their becoming-body through the very act of being cut.

As central as drawing is to Sayal-Bennett’s practice, the artist also critically attends to the ways in which the medium re-enacts and extends the purview of the cut. It is through drawing, even, that the fields of medicine and architecture are ideologically co-extensive. The very appearance of the architectural ‘cutaway’ and ‘flat plan’ by the Renaissance period has much to do with the anatomically disassembled body, [1] and both deal with a biopolitics in the senses of potential and manipulation. It is such that the status of the body is and can be projected onto both human and non-human objects of analysis. A function of mapping, planning and documentation, drawings isolate one part of an organism from its greater, coordinated whole. A part is alienated and cordoned off to analysis, for the cut includes to the exclusion of all else; to quote the artist, it ‘denaturalises relations’.[2]

Of relations: there is impetus in the inter-generational pattern. Sayal-Bennett’s grandmother did her medical training in Lahore before moving to London, a knowledge which she combined with an ayurvedic practice that conceives of the body holistically. Sayal-Bennett’s mother, on the other hand, would turn to psychology after refusing to dissect animals. Further still, the divergent courses of the three women speaks of the cut as a force of division: an invocation, perhaps, of the 1947 partition of British India. The exchange between coloniser and colonised troubles the sanitised story of Western medical progress, which too comfortably omits prejudicial scrutiny and the invasive use of bodies deemed less-than-human for study.[3] The ‘part’ acquires altered resonance to those that contend with dislocation or displacement, for it begs the diaspora’s question. No longer merely a term in a conceptual apparatus, the ‘part’ becomes cross-hatched by issues of difference, localisation and the discontinuous self.

The whiteness of an art gallery’s walls is no accident, insofar as white succeeds in neutralising and cancelling out the unsightly textures of the external world. Texture is difference, and difference is abrasion or noise that must be obnubilated, at very least reduced to unfeeling. White is both Le Corbusier’s nerve-soothing anaesthetic[4] and the amnesiac’s cool which, in the gallery context, furnishes us with a stately reverence for the contemporary work of art. It is within this setting that Sayal-Bennett points to another form of optical hygienics by referring to Hermann Von Helmholtz’s ophthalmoscope, a device that granted seeing into the recesses of the eye. Vision is extended through technology’s reach into the body; like all discoveries, the body has been ushered along a passage from obscurity to light. Treating sight as a miracle withheld by the eye – because enclosures necessarily keep secrets – the ophthalmoscope is vision-engineered medicalisation par excellence. At last, even the eye can be turned inside out and transformed into the surface of so many images.

Again, we find ourselves at the level of surface: the surface which is equally the section that has been exposed by a cut. ‘In their digital form, my drawings are instructional – a line becomes a vector, a tool path a machine can follow,’ Sayal-Bennett remarks of the diagrams she must create in order to, for example, laser-cut steel.[5] The perfect edge is born of the perfect incision and it is said that emotions needlessly complexify, worse still fail, decision-making and performance. We may understand an affectless cut as one that is removed from its inherent violence, one that bears no risk or responsibility for the divides it creates, nor the parts that result. But it is the exacting trace that is the perfect crime, because it marries a cut to drawn line and betrays nothing in the superimposition.

Elaine ML Tam

[1] Beatriz Colomina, X-Ray Architecture (Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2019)

[2] Amba Sayal-Bennett, in an unpublished conversation with the writer, 1 March 2025.

[3] Rose Marie San Juan, Violence and the Genesis of the Anatomical Image (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2023)

[4] Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, Are We Human? Notes on an Archaeology of Design, (Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2016)

[5] From unpublished artist notes shared with the writer, 25 February 2025.

Amba Sayal-Bennett (b. 1991, London) lives and works in London. Sayal-Bennett received her BFA from Oxford University, and her MA in Sculpture from the Royal College of Art. She was awarded her PhD in Art Practice and Learning from Goldsmiths and has published her practice-based research with Tate Papers. Between January and March 2022, she was The Derek Hill Foundation scholar at the British School at Rome in Italy.

Recent exhibitions include Drawing Room Invites (upcoming solo), Drawing Room, London, (2025); Artist’s Rooms, Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai (2024); Geometries of Difference, Somerset House, London (2022); Horror in the Modernist Block, IKON, Birmingham (2022); My Mother Was a Computer, Indigo+Madder, London (2022); and Tomorrow, White Cube, London (2021).

SELECTED WORKS

INSTALLATION VIEWS

To request a catalogue or receive further information, please get in touch: info@indigoplusmadder.com

Hyperspect, 2025

Powder coated metal, magnets and fabric

29 x 32 x 1.5 cm